|

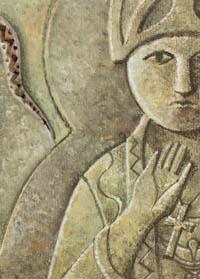

Saints and Scholars

Irish history really begins with Saint Patrick, who converted Ireland to Christianity. The

son of a civil servant in Roman Britain, he was abducted and sold into slavery

in County Antrim. Escaping to the

European mainland, he eventually returned to Ireland as a missionary and

bishop. His first church was at Saul, in County Down, and he later made Armagh

the ecclesiastical capital of the island, as it has remained. Traditionally his

arrival in Ireland has been dated 432 AD, but some scholars believe it was much

later in the fifth century and that he completed the work begun by an earlier

missionary.

Whatever the truth of this, Christianity provided not merely a

religion but also a written language, Latin. A tradition of story-telling had

preserved accounts of great events, tribal histories and genealogies. Now there

were scholars who recorded this material on vellum manuscripts, no doubt

amending and embroidering it as they blended fact and legend. Such laborious

work was aided by the spread of monasteries, often on isolated islands or

mountains, where monks lived austerely and could pursue their studies free from

the demands placed on conventional priests.

Ireland, situated at the western edge of Europe, was certainly inhabited as early

as 6,000 BC. Archaeology provides evidence of successive invasions, hunters and

fishermen followed by fanners using stone tools to clear land, then by tribes

skilled in metalwork. The last pre-Christian invaders were the iron-using Celts

or Gaels, who reached Ireland around 600 BC. More than 1,000 years later, it

was a well-established pagan Celtic society which accepted Christianity.

|

Fifth-century Ireland was divided into a number of small kingdoms.

The more influential kings received tribute from the weaker ones, but the idea

of a high king of Ireland is a later invention. The Celts were cattle fanners,

wealthy enough to devote some resources to intricate gold and silver ornaments,

sophisticated enough to have lawyers (brehons) and poets (filidh)

as well as the druids who practised magic and offered sacrifices to the pagan

gods. They had their own language, from which modem Irish has evolved. Kings

were elected, but from a narrowly defined group possessing royal blood. Wars were common, and the balance of power

between kingdoms shifted constantly.

Saint Patrick divided Ireland into dioceses, but before long abbots

became more influential than bishops. The monasteries were important seats of

learning at a time when the European mainland was entering a dark age following

the collapse of the Roman Empire. In time Irish monks set out to spread the

Christian message in foreign countries. Among them were Saint Columba, who

founded a famous monastery on the Scottish island of lona, and Saint

Columbanus, who founded monasteries in France, Germany and Italy.

Ireland had escaped invasion by the Roman legions, but it could not

escape the Viking longboats which menaced its coasts and rivers in the ninth

century. But, while the Norsemen sacked monasteries, they also settled as

traders and founded settlements which grew into such cities as Dublin, Cork and

Limerick. The Celtic kingdoms

eventually fought back, and in 1014 Brian Boru, who had claimed the high

kingship, won a decisive victory over the Norsemen at Clontarf, near Dublin.

By now the Church was in disarray, the monasteries corrupt and the

dioceses ineffective. However, the establishment of Cistercian monasteries from

1142 on, and the reorganisation of the Irish Church at the Synod of Kelts in

1152 set reforms in motion. The petty kingdoms remained a source of disunion.

Brian Boru had been killed at Clontarf, and successive aspirants to the high

kingship were unable to enforce their authority. The land of saints and

scholars lacked military and political cohesion, and was in no condition to

repel the next invaders who sailed for Ireland.

|