|

The 1798 Rising

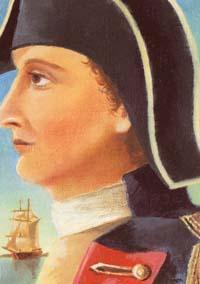

The Society of

United Irishmen was founded in Belfast in 1791. Its inspiration was a young Dublin lawyer, Theobald Wolfe Tone,

who was invited to Ulster after publishing a pamphlet entitled "An

argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland". Northern Presbyterians

also suffered from religious discrimination, though less severely, and had

absorbed republican ideas from the American and French revolutions. With the

formation of a Dublin society, pressure for reform grew, and relief acts were

passed in 1792 and 1793. However, Tone sought revolution rather than reform,

and hoped for French help in severing the link with Great Britain. After

Britain and France went to war in 1793, the United Irishmen came under

increasing pressure from the government. Tone chose exile in America in

preference to being prosecuted for treason, and the United Irishmen evolved

into a secret society bound by revolutionary oaths.

Returning to Europe in 1796, Tone persuaded the French to invade

Ireland, but bad weather prevented a landing. Despite this setback, the United

Irishmen continued to recruit members, particularly among disaffected Catholic

peasants. Meanwhile, the government had

passed an act providing for harsh measures against those who held illegal arms

or administered illegal oaths. An army under General Lake conducted an

oppressive campaign to disarm Ulster, seen as the most dangerous province. The

government had many informers among the United Irishmen, and in March 1798 most

of the Leinster leaders were arrested in Dublin. The only leader of the United

Irishmen with military experience, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, was captured on 19

May, four days before the date fixed for the rising.

|

Apart from some short-lived but bloody skirmishes in

towns and villages west of Dublin, the rising was confined to the northern

counties of Antrim and Down, and to County Wexford. The Wexford rising, which

began on 26 May, was a spontaneous and frightened response to the cruel

measures of magistrates searching for arms and conspirators, but the rebels in

turn committed acts of great savagery. They found a remarkable leader in Father

John Murphy of Boolavogue, who quickly assembled an army of Catholic peasants

equipped with muskets and pikes. The few troops were outnumbered and poorly

led, and the rebels soon commanded most of the

county. The government was slow to react, but the rebels' attempts to spread

the rising to neighbouring counties were halted by defeats at Arklow and New

Ross. On 21 June, General Lake stormed the rebel headquarters at Vinegar Hill,

near Enniscorthy, and resistance soon ended.

Murphy was later captured and executed.

In Ulster, where the rebels were mainly Presbyterians, the rising

began later and was soon over. On 7 June, some 3,000 men attacked the garrison

in Antrim town. An informer had revealed their plans, however, and

reinforcements soon arrived to scatter the rebels, who fled to their homes.

Their leader, Henry Joy McCracken, was captured and hanged. In County Down the

rising came to an end on 13 June, when the United Irishmen were defeated at

Ballynahinch. Their leader, Henry Monroe, was also hanged.

Meanwhile, Wolfe Tone had persuaded the French government to send

another expedition to Ireland, but it sailed from La Rochelle long after the

rising had been defeated. On 23 August, 1,000 French troops under General

Humbert landed at Killala Bay in Connacht. Local peasants swarmed to his

banner; however, after an early victory at Castlebar, he surrendered on 8

September to the superior army of the Marquis Comwallis, who had been appointed

lord lieutenant and commander-in-chief in anticipation of a rising. Tone

himself was captured in October aboard a French ship in Lough Swilly.

Court-martialled in Dublin, he pleaded for a soldier's death before a firing

squad, but was sentenced to be hanged. He committed suicide in prison on 19

November 1798.

|