|

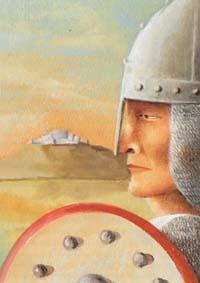

Norman conquest

At the beginning of

May 1169, three single-masted longships beached at Bannow Bay, County Wexford.

They had sailed from Milfordhaven in Wales, and on board were Normans, Welshmen

and Flemings. Their leader was Robert FitzStephen, a Welsh warlord, and they

made camp on Bannow Island, separated from the mainland by a narrow channel

which has since silted up. A day later, two further ships arrived under the

command of Maurice de Prendergast, bringing their numbers to around 600. They

were soon joined by 500 Irish warriors led by Dennot MacMurrough, King of

Leinster. A century had passed since the Battle of Hastings, when William the

Conqueror had launched the Norman invasion and systematic colonisation of

England. Now the Norman conquest of Ireland had begun.

The invasion of 1169 sprang from the long-standing enmity of Dennot

MacMurrough and Tieman O'Rourke of Breifne, a more northerly kingdom. Dennot

had once abducted Tieman's wife Dervorgilla, and in 1166 Tieman sought revenge.

Dermot, forced out of his headquarters at Ferns, fled to England. He landed at

Bristol, and eventually made his way to Aquitaine in France, where he

appealed to

Henry II for help. Although he was King of England, Henry was a French-speaking

Norman much preoccupied with controlling his French territories. However,

he had contemplated

an invasion of

Ireland as early as 1155, with the approval of the only English Pope, Adrian

IV, and he readily authorised Dermot to seek allies among the Norman lords in

Britain.

|

Returning to Bristol, Dermot was initially unsuccessful, so he

turned his attention to Wales, where the Normans were perpetually engaged in

warfare against the native Welsh. Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, Earl of

Pembroke, proved an attentive listener. Pembroke, known as Strongbow, was an

experienced campaigner, but he had fallen out of favour at Henry's court.

Ireland offered an opportunity to restore his standing and add to his wealth,

but he put a price on his assistance. He was to marry Dermot's daughter Aoife,

and in time succeed to the kingship of Leinster. With Strongbow's approval,

Dermot won the support of FitzStephen and other Welsh-Norman lords, to whom he

promised grants of land. He returned to Ireland with a small army in 1167, but

was defeated by his old enemy Tieman O'Rourke and forced to pay one hundred

ounces of gold in reparation for the abduction of Dervorgilla, Two years later,

it would be a different story.

From Bannow the combined armies headed towards Wexford, a Norse

seaport some twenty miles away. There was a brief skirmish at Duncormick,

before the assault on Wexford's walls. After some resistance, the Norsemen

acknowledged the superiority of the armoured knights and their archers and

surrendered the town. A year later, in response to a plea from Dermot,

Strongbow despatched a small

force under Raymond le Gros. It landed at Baginbun, near Bannow, and

immediately routed a strong army of Irishmen and Norsemen from Waterford,

inspiring the couplet: "At the creek

of Baginbun, Ireland was lost and won." Strongbow himself arrived with

1,200 men in August 1170, stormed Waterford, where he married Aoife

MacMurrough, and within a month had captured Dublin.

With Dermot's death in May 1171, Strongbow became King

of Leinster, and his skilful knights and archers continued to defeat larger

Irish and Norse armies. The arrival of Henry II in October 1171 launched a new

phase of the conquest. By grants of land, the King encouraged his barons to

gain control of most of Ireland, marking their advance with formidable castles.

A justiciar or king's lieutenant was appointed to head a central government in

Dublin. Irish parliaments were occasionally summoned, and from 1297 included

elected representatives. However, Gaelic resistance to the Norman conquest was

never wholly eliminated, and the foundations were laid for eight centuries of

Anglo-Irish conflict.

|