|

Independence

The principal

beneficiary of the 1916 rising was Sinn Fein (Ourselves Alone), a political movement

founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith. Griffith, who opposed the use of force,

argued that the Irish MPs should quit Westminster, set up their own assembly in

Dublin, and make British government unworkable. As public opinion turned

against the Irish parliamentary party, Sinn Fein won several by-elections in

1917. Among its successful candidates was Eamon de Valera, who had fought in 1916,

and he soon succeeded Griffith as president of Sinn Fein. When a general

election was held in December 1918, Sinn Fein won seventy-three of the 105

Irish seats, most of the rest going to the Unionists.

Many of the successful Sinn Fein candidates were in prison in

England. However, on 21 January 1919 twenty-five members met in Dublin as Dail

Eireann (Assembly of Ireland) and adopted a declaration of Irish independence

committing themselves to the republic which had been declared in 1916. On the

same day, the War of Independence began when two policemen were killed by

Volunteers in County Tipperary as they guarded a consignment of gelignite. The

Volunteers, who now became known as the Irish Republican Army, continued to arm themselves through attacks on police barracks and army depots.

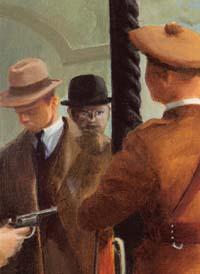

The principal figure in the IRA was Michael Collins, who had fought

in the GPO in 1916. Collins built up a

formidable intelligence network, together with a special squad which

assassinated

British intelligence officers and key Irish detectives. Elsewhere, men like

Ernie O'Malley and Tom Barry perfected guerilla tactics, with mobile

"flying columns" that carried out surprise raids. In 1920 the British

government reinforced the Irish police with ex-soldiers known as Black and

Tans, wearing a mixture of police and army uniforms, and later with ex-officers

known as Auxiliaries. Atrocities were committed by both sides and much property

was destroyed, including many country houses owned by Anglo-Irish gentry.

|

By 1920 the British government, led by David Lloyd George, was

prepared to seek a compromise which would keep Ireland within the British Empire

but make concessions to Irish nationalism. A new Government of Ireland Act

provided for a measure of home rule to be exercised by two parliaments in

Ireland, and in a general election unopposed Sinn Fein candidates took all but

four seats in "Southern Ireland". Since Sinn Fein was unwilling to

enter the new Dublin parliament, Lloyd George offered de Valera negotiations on

the future of Ireland. The two sides agreed on a truce, and on 11 July 1921 the

War of Independence ended.

Later in the month, when de Valera met Lloyd George in London, he

refused to accept the terms offered by the British prime minister. When the

second Dail met in August it elected de Valera president, and

thereafter negotiations with the British government were conducted by a delegation

led by Arthur Griffith. On 6 December 1921, after protracted discussions and

faced with Lloyd George's threat to resume hostilities in Ireland, the weary

delegates agreed to a treaty providing for an "Irish Free State" with

dominion status, and allowing the six counties of Northern Ireland to remain

within the United Kingdom.

The treaty also provided for an oath of allegiance to the crown,

which de Valera refused to accept. When in January 1922 the Dail approved the

treaty by sixty-four votes to fifty-seven, he ceded the presidency to Griffith.

Collins was appointed head of a provisional government. Though unhappy with the

treaty, he rightly believed it opened the way to greater freedom and

independence, and his views were substantially endorsed in a general election.

De Valera still refused to accept the treaty, however, and the inauguration of

the Irish Free State was marked by a civil war which lasted until the

anti-treaty republicans conceded defeat in May 1923.

|