|

Grattan's Parliament

For most of the

eighteenth century, the Irish parliament in Dublin was prepared to accept a

subordinate role. In return, England would always defend Protestant interests

in Ireland. Under Poynings' Law, passed in the fifteenth century, no Irish act

could pass without the approval of the king and his advisers in England. The

viceroy in Dublin Castle was a member of the British government. In 1720, a

Westminster act known as "the Sixth of George I" gave the British

parliament the right to pass laws for Ireland. The only weapon of the Irish

house of commons, now wholly Protestant and largely controlled by wealthy

landlords, was its powers of taxation.

Irish agriculture was generally inefficient, and manufacturing

trades suffered from restrictions imposed to protect English merchants. British

policies were challenged by writers such as Jonathan Swift, Bishop George

Berkeley and Charles Lucas, founder of the Freeman's Journal. Within the

Irish parliament itself, a reforming group known as "patriots"

eventually emerged, led by Henry Flood and the Earl of Charlemont. They

believed that a more representative assembly would, while preserving the

Protestant interest, achieve more for Irish commerce.

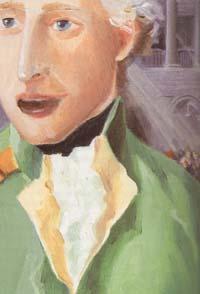

In 1775 Flood accepted a government post, and leadership of the

patriots passed to Henry Grattan, a young lawyer whom Charlemont had brought

into parliament. With the outbreak of rebellion in the American colonies,

followed by French and Spanish intervention, Britain was forced to withdraw

troops from Ireland. Fears of a French invasion led to the formation of a

Protestant militia, the Volunteers. Charlemont became their leader, and the

Volunteers threw themselves behind the demands for reform. Bending to Grattan's

oratory, a fearful government removed most of the trade restrictions in 1779,

and in 1782 Irish parliamentary independence was conceded. Westminster repealed

the 1720 act, and the Irish parliament removed the most oppressive parts of

Poynings' Law.

|

"Grattan's parliament" is the name usually

given to the two decades of parliamentary independence which ended with the Act

of Union in 1800. Certainly, there was much celebration in 1782, and parliament

voted its hero 50,000 pounds in gratitude. The final years of the century saw great

commercial activity, and a prosperous Dublin acquired many of the handsome Georgian

buildings for which it is noted

today. However, Grattan soon faced a challenge from the embittered Flood, now

out of office, who questioned Grattan's achievement and forced a further

Renunciation Act from Westminster in 1783. In November 1783, a Volunteer

convention in Dublin drew up a plan for parliamentary reform which Flood

presented as a bill. It was immediately rejected by the Irish parliament, whose

members refused to be coerced by an armed assembly, and the convention

dispersed. The unity of the

"Protestant nation" had been destroyed, and the Volunteer movement

gradually disintegrated.

To its credit, the Irish parliament eased the penal laws, and in 1793

Catholics gained the right to vote. However, a property qualification

restricted the franchise, and the bulk of seats were still controlled by a few

wealthy Protestants. Nor were Catholics allowed to sit as MPs. It was a

fundamentally unstable position, given that the population was overwhelmingly

Catholic, and far-sighted Protestants began to consider that their ascendancy

could only be maintained in a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The

rebellion of the United Irishmen in 1798 convinced the government of the need

for change. When its first Bill of Union was rejected by the Irish house of

commons, the government embarked on a cynical programme of bribery, buying

votes with offers of titles, government posts and compensation. In 1800, dressed

in Volunteer uniform, an ailing Grattan begged the commons not to agree to the

Union. For once his oratory was in vain, and parliament voted itself out of

existence.

|