|

The Easter Rising

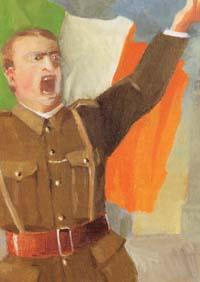

On 24 April 1916,

Patrick Pearse stood outside the General Post Office in Dublin and read a

proclamation announcing the establishment of an Irish republic under a

provisional government. Among the seven signatories of the proclamation was

James Connolly, head of the para-military Irish Citizen Army, who had earlier

led a successful occupation of the building. Elsewhere in Dublin, armed men had

taken over key points such as the Four Courts, the College of Surgeons

overlooking St Stephen's Green, and Boland's Mills. It was Easter Monday, and

there were few people in the centre of Dublin to witness the rising. Many army

officers had gone to the Fairyhouse races.

Almost all the revolutionary leaders were members of the secret

Irish Republican Brotherhood. The outbreak of war had persuaded them that in

England's difficulties lay Ireland's opportunity. As earlier rebels had looked

to France for help, they now turned to Germany, which promised to send arms. In

addition to the small Irish Citizen Army, formed in 1913 to defend workers

against police harassment, there were thousands of Irish Volunteers, a body

formed in response to the Ulster Volunteer Force. Like the UVF, the

Volunteers carried out a successful gun-running exploit, landing arms at Howth,

near Dublin, a few days before war was declared.

The Volunteers had been infiltrated by members of the IRB, which had

secretly fixed Easter Sunday as the date for the rising. The Volunteers'

leader, Eoin MacNeill, only discovered the plan on 20 April. Two days later, he

learned that a German ship bringing arms had been scuttled. Realising that a

rising was doomed to failure, he cancelled all Volunteer manoeuvres. Despite

this setback, and knowing that their forces would be limited to a modest number

of Dublin Volunteers as well as the ICA, Pearse and Connolly decided that a

rising must take place, if only as a blood sacrifice to arouse the Irish

people.

|

Once the rebels had occupied some of their targeted buildings, they

had nowhere to go. The rest of Ireland

showed little disposition to join the rising, apart from a few minor outbreaks

of violence, and in Dublin there were few recruits. The government, which had

not expected a rising, responded quickly by declaring martial law. The army in

Dublin was reinforced, and heavy artillery was deployed against the republican

strongholds. On Friday, General Sir John Maxwell arrived from England to assume

overall command, and made it clear that he would not hesitate to destroy every

building held by the rebels. The GPO, headquarters of the rebels, was soon in

flames. On Saturday afternoon, Pearse agreed to Maxwell's demand for

unconditional surrender.

In different circumstances the rebels might have been treated more

mercifully, but Britain was at war, and the army and police had suffered

greater casualties than Pearse's men. Ireland was still under martial law, and

Maxwell was at liberty to inflict retribution. On 3 May, just four days after

the surrender, a terse announcement was made that Pearse and two other

signatories of the republican proclamation had been tried by court martial and

shot. By 12 May the total of executions had reached fifteen, including Connolly

and the three other signatories. Another seventy-five rebels had the death

penalty commuted to penal servitude, including Countess Constance Markievicz,

who would later become the first woman elected to the Westminster parliament.

In halting the executions, the government was responding to a wave

of public revulsion, but the damage had been done. Ireland had a new gallery of

martyrs, and earlier apathy or even hostility towards republicanism was

replaced by sympathy for the independence cause. Of some 3,400 arrested following the surrender, more than half

were imprisoned or interned in England, where they plotted a new onslaught on

British rule.

|