|

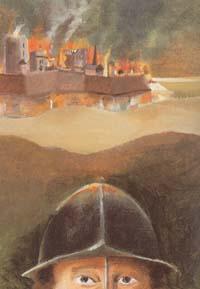

The Curse of Cromwell

On I5 August 1649

Oliver Cromwell landed at Ringsend, near Dublin, with an army of 3,000

battle-hardened Ironsides. The civil war in England had ended, and King Charles

I had been executed seven months earlier. In Ireland, however, the Roman

Catholics had been in revolt since 1641 and held much of the island. They had

generally taken the King's side, though some had seen in England's turmoil a

chance to restore Irish independence. Cromwell entered Dublin as "lord

lieutenant and general for the parliament of England". A fanatical Protestant,

he intended to offer no quarter to papist rebels who had massacred English and

Scottish settlers. In Ireland, he could use confiscated land to pay off debts

to his troops and to the so-called "Adventurers" who had financed the

parliamentary cause.

From Dublin Cromwell marched north to Drogheda, which was defended

by an English Catholic and royalist, Sir Arthur Aston. When his surrender

demand was ignored, Cromwell stormed the city and ordered the death of every

man in the garrison, describing this as "a righteous judgment of God upon

these barbarous wretches". The nearby garrisons of Dundalk and Trim took

flight. Having secured the route to Ulster, Cromwell turned on the

south-eastern port of

Wexford, this time slaughtering townspeople and garrison alike. Neighbouring

towns quickly submitted.

Cromwell's campaign ended with an assault on Clonmel where, after

stout resistance, the defenders withdrew by night. In May 1650 he returned to

England, leaving his son-in-law, Henry Ireton, in command. Within two years

Catholic resistance was at an end. Many Irish soldiers were allowed to seek

their fortunes in Europe. Catholic land-owners were largely dispossessed, but

some were given the option of settling on less fertile land in Connacht.

Cromwell himself had been in Ireland a mere nine months, but his brutality left

an indelible impression on the native Irish. "The curse of Cromwell on

you" became an Irish oath.

|

The rebellion of 1641 had made an equal impression on the Protestant

settlers in Ulster. The plantation of Ulster had been entrusted to three

classes of land-owner. From England and Scotland came "undertakers",

who were required to bring in their tenants. Secondly, there were

"servitors", who had served the Crown in Ireland, and who were

allowed to take Irish tenants as well as newcomers. Finally, some native Irish

were allowed to own land, if they were deemed trustworthy and agreed to adopt

English farming practices. In the event, too few immigrants were attracted to

Ireland, and the undertakers found they had to accept Irish tenants. This

intermingling of the two religious groups was to prove a dangerous cocktail.

The worsening conflict between King and parliament in England

encouraged the native Irish to seek to recapture their forfeited lands. They

were also impelled by a fear that if the Puritans triumphed

in England, the Catholic religion would be suppressed. On 23 October 1641 a

series of uprisings in Ulster spread panic among the Protestant settlers. Those

who were not killed by the rebels fled for safety into the defended towns,

where plague and starvation soon took their toll. Modem historians suggest that

first accounts of the rebellion exaggerated the number of deaths and the extent

of atrocities committed by the native Irish. Wherever the truth lies, the

rebellion created in Protestant minds a distrust of their Catholic neighbours

which has survived to modern times.

The hostilities gradually spread throughout Ireland, and

in 1642 a Catholic government was formed in Kilkenny. The rebels found an experienced

commander in Owen Roe O'Neill, nephew of Hugh O'Neill, who won a famous victory

at Benburb in 1646. However, the Catholic cause was always prone to internal

dissension, and O'Neill died before he could test his generalship against

Cromwell.

|